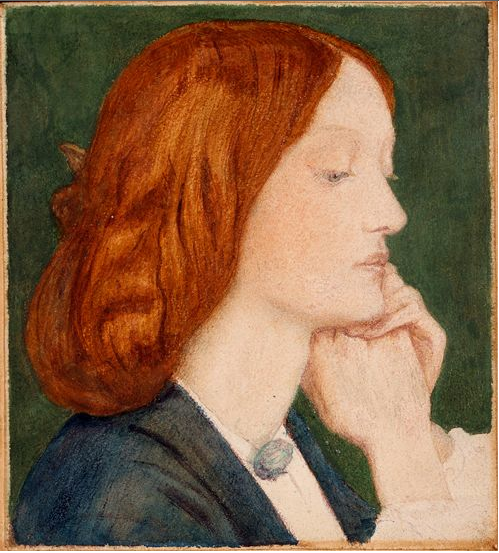

Lady Clare. (1857). Signed and dated “EES/57”. Watercolor on paper. Private collection.

The literary reference for this painting was Tennyson’s Lady Clare from Poems (1842). Siddal may have first seen the poem in a newspaper, and her interest in the poet eventually led her, Millais, Hunt, Rossetti, and others to illustrate his 1857 edition of Poems. Siddal’s designs included St Cecilia from The Palace of Art and Jephtha’s Daughter from A Dream of Fair Women. Lady Clare was the only painting completed as it was worked up from studies, a typical technique of Pre-Raphaelite artists in the 1850s (Marsh and Nunn 116).

In the story, the natural mother of the heroine begs her daughter to conceal her humble origins so Lord Ronald won’t withdraw his offer of marriage. Lady Clare refuses:

“”If I’m a beggar born”, she said,

“I will speak it out, for I dare not lie.

Pull off, pull off the brooch of gold

And fling the diamond necklace by”.

“Nay now, my child,” said Alice the nurse,

“But keep the secret all ye can.”

She said, “Not so; but I will know

If there be any faith in man.””

(Marsh and Nunn 116).

There may be a personal connection to this poem and watercolor for Siddal. A fear of being rejected for marriage by D.G. Rossetti may have been a lingering fear due to their class difference (Marsh and Nunn 116). The fear was unnecessary though, as they married in spring of 1860 (Prettejohn 191). The poem concludes happily too, as Lord Ronald does not reject his bride due to her lower class standing (Marsh and Nunn 116).

The Victorian interests in medieval art and architecture is evident here. The viewer catches a glimpse of the castle’s stairway through the partially opened door and the stained glass window captures the viewer’s attention with its bright colors. The stained glass references the Judgement of Solomon and when a true mother reveals herself (Marsh and Nunn 116).

Siddal studied Gothic art and medieval manuscripts, likely at John Ruskin’s house or the British Library. Because of this, there is an awkwardness to her figures, perspective, and compositions (Prettejohn 190). In this particular watercolor, Lady Clare’s attire is derived from manuscripts viewed at the British Museum (Marsh and Nunn 116).

In 1984, the Tate Gallery included this piece in its exhibition and it was critically discussed for its gender imagery, inter-texuality, and Pre-Raphaelite compositional practice (Marsh and Nunn 116).

Works Cited

“Elizabeth Eleanor Siddal”. Pre-Raphaelite Art. 4 Mar. 2009. Web. 6 Mar. 2013. http://preraphaelitepaintings.blogspot.com/2009/03/elizabeth-eleanor-siddal-lady-clare.html

Marsh, Jan, and Pamela Gerrish Nunn. “Pre-Raphaelite Women Artists”. London, Thames and Hudson: 1997. Print.

Prettejohn, Elizabeth. The Cambridge Companion to the Pre-Raphaelites. New York, Cambridge University Press: 2012. Print.