Women artists who portrayed the female nude during the late nineteenth century ran the risk of being pegged into two categories. These women were viewed as being morally decadent, or surprisingly, as being politically conservative because they were following the classical revival movement, which was popular at the time. De Morgan’s use of the female nude stood for allegorical purposes, which often tackled the dissatisfaction women felt from their stifling roles in life (Smith 60-61).

During the first decade of her career, her focus wasn’t on the allegorical as much as it was on producing paintings from sources that were more traditionally biblical, mythological, or literary. From her first study trip to Rome in 1875, to her marriage to William De Morgan in 1885, her early work from this decade can broadly be categorized as history paintings, which is an oddity for a woman artist.

First of all, history paintings were perceived as being superior because of the required education needed to produce one. This knowledge included training with the classics, becoming acquainted with contemporary European literature, and years of drawing from a model that was both draped and nude. This education was the standard for men, but De Morgan was a fortunate young lady and received the same education at home as her brothers. This included learning Greek, Latin, French, German, and Italian, while reading classical mythology and literature. From here, she was given the opportunity to study art at the Slade School of Art, but was not allowed formal training with a fully nude model (Smith 63).

Another aspect that links her aspiration to becoming a professional painter is her skillful use of oils and not watercolors (which were deemed suitable for women) (Smith 65).

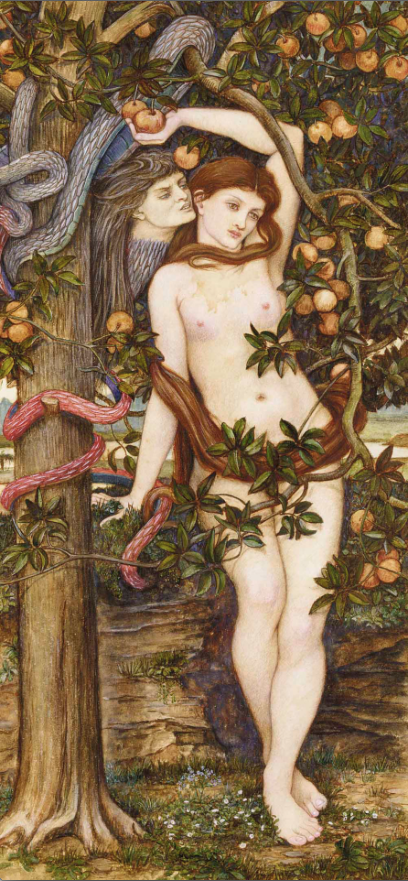

In 1877, she exhibited Cadmus and Harmonia at the Dudley Gallery (Smith 65). Studying the work, I immediately thought of Eve and the serpent, but I discovered that the title didn’t fit. In the painting, a fully nude woman stands directly in the center of the painting as if on display. She also looms close to the foreground and seems overly large when compared to the rocky formations around her. She looks sadly off to the side, as if thinking about an old memory or past lover. We see no sign of human inhabitation, only a sprinkling of small flowers at her feet, and calm water to her left. The snake has coiled around both of her feet, anchoring her in place and moves upwards, ready to complete his task of captivating her.

After doing research on this painting, I discovered many other references. The woman’s pale skin, painted with a touch of silvery gray, echoes the underside of the snake’s belly. Visitors likely cringed at the thought of a woman’s bare skin touching that of a snake’s. The late Victorian viewer was more aware of the emotional connection and not the intellectual one. A general, erotic associated would have been assumed, from Eve and Lilith to Lamia and Flaubert’s Salammbo (Smith 63).

The narrative of Cadmus and Harmonia focuses on the devotion between an elderly married couple in a moment of sorrow. However, as we can plainly see, Harmonia is a beautiful young lady, not an old woman (Smith 63). Ovid wrote that Cadmus encountered the king of Phoenicia, and “a serpent sacred to Mars” who killed Cadmus’s attendants. Finally, after struggling to destroy the serpent, Cadmus succeeds, but then hears a voice say “Thou too shalt be a serpent for men to gaze on.” Years later, after marrying Harmonia (daughter to Venus and Mars), and having several of their children and grandchildren die, Cadmus said: “Was that a sacred serpent which my spear transfixed long ago…? If it be this the gods have been avenging with such unerring wrath, that I pray that I, too, may be a serpent, and stretch myself in long snaky form.” Harmonia, distraught at his transfiguration, embraces his serpentine form as it snakes up her body and begs the gods to transform her into a serpent also. “She spoke; he licked his wife’s face and glided into her dear breasts as if familiar there, embraced her, and sought his wonted place about her neck. All who were there-for they had comrades with them-were filled with horror. But she only stroked the sleek neck of the crested dragon, and suddenly there were two serpents there with intertwining folds.” An excerpt of Ovid’s passage was placed with De Morgan’s exhibition of Cadmus and Harmonia (Smith 65).

I find it interesting that even though there were comrades present during this transfiguration phase, De Morgan chose to portray only the serpent and Harmonia. I believe it fits nicely with her spiritual ideals because now the viewer focuses solely in on Harmonia and gets the sense of transformation that must be taking place inside of her; how her soul changes in addition to her body.

Looking back, we wonder why De Morgan chose such an elusive female figure-why not Venus, the obvious classical choice? We must assume that she was once again flaunting her superiority; she had a diverse education that went beyond the superficial knowledge of the classical subjects and wanted to make this known (Smith 65).

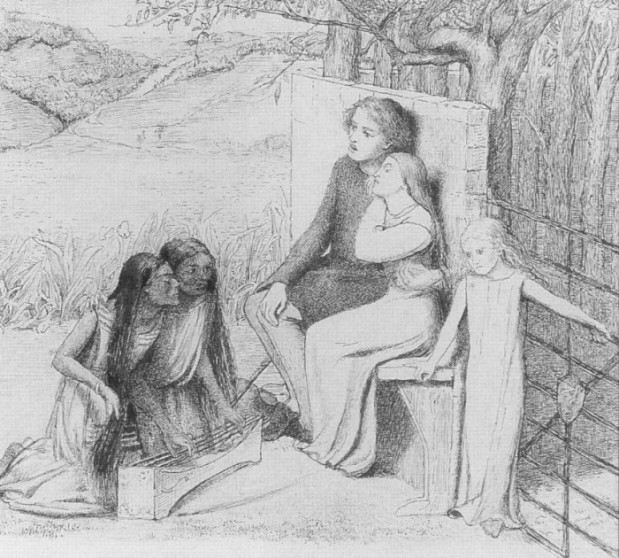

Women artists during the Late Victorian period were encouraged by their male mentors to portray the nude female as “a submissive decorative being.” De Morgan would have known this and a simple glance at this painting seems as if she went along with the idea, if for professional reasons only. However, upon closer examination of her work and dissection of the myth, Harmonia has been recreated as the protagonist and as a symbol of spiritual transcendence. When compared with Spencer-Stanhope’s Eve Tempted by the Serpent, (c. 1877) the viewer can see the submissive female nude portrayed (Smith 65). To me, it looks like she has no strength or willpower to avoid what is going to happen next. She also is portrayed sitting down, which goes along with the submissive theme because she isn’t supporting herself, and could be easily swayed. Her facial expression also suggests that she has already been brainwashed by the serpent, and offers no hint of resisting his poisonous words (she already has the fruit in her hand too)!

Works Cited

Smith, Elise Lawton. Evelyn Pickering De Morgan and the Allegorical Body. London: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2002. Print.